7 Stages of Dementia: Everything You Need To Know

Article at a glance

Dementia currently affects over 55 million people worldwide.

Dementia is a group of conditions that affect the ability to think, remember, and make decisions.

Dementia symptoms are often difficult to notice in the early stages and can take some time before being diagnosed.

There is currently no cure for dementia, though treatments can help manage symptoms.

What is Dementia?

As defined by The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), dementia is “not a specific disease but is rather a general term for the impaired ability to remember, think, or make decisions that interfere with doing everyday activities.” There are a few different conditions that fall under this category, including Alzheimer’s disease.

While dementia is somewhat common (55 million people currently live with dementia worldwide, according to the World Health Organization), it’s not a normal part of aging. There isn’t currently a cure for types of dementia, and symptoms tend to worsen as the disease progresses. Dementia tends to occur in stages known as mild dementia, early-stage dementia, middle-stage dementia, late-stage dementia, and severe dementia.

Types of Dementia

There are a few different conditions that fall under the category of dementia—some more common than others.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is the most well-known and most common form of dementia and accounts for 60 to 80 percent of all dementia cases. It impacts memory, cognitive ability, and behavior.

Some symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease include:

Difficulty remembering new information

Memory loss

Losing track of dates or current locations

Struggling to complete daily tasks

Poor judgment

Losing things or misplacing them repeatedly

There is still much to learn about Alzheimer’s disease, but it is speculated that the cause has to do with unnatural protein buildup around brain cells.

Note: To learn more about Alzheimer’s disease, visit this source.

Lewy Body Dementia

Dementia with Lewy bodies results from proteins that clump up in the cortex of the brain. While the precise cause is unknown, we know that there is an association with the loss of certain neurons that produce important brain chemicals (one of which is tied to memory and learning). Lewy body dementia is another common form of dementia.

Symptoms of Lewy body dementia include:

Visual hallucinations

Severe loss of thinking and cognitive decline

Difficulty balancing or moving

Difficulty sleeping/sleep disturbances

Frontotemporal Dementia

Frontotemporal dementia (also referred to as frontotemporal disorders or FTD) results from damage to neurons in the frontal and temporal parts of the brain. The official cause is unknown, though genetics (those with a history of family members with FTD) accounts for 10–30% of cases.

Symptoms of FTD can vary but may include:

Issues with planning and problem solving

Constant repetition of the same words or actions

Difficulty speaking or moving

Behavioral changes (disinterest in things they once loved, mood swings, etc.)

Difficulty concentrating or prioritizing tasks

Vascular Dementia

Vascular dementia occurs due to damage to blood vessels in the brain and results in changes to memory and behavior. There isn’t an official cause, though there have been some potential connections between those who have experienced strokes or who have cardiovascular disease.

Symptoms of vascular dementia include:

Difficulty performing tasks that were once done easily (paying bills, etc.)

Memory loss

Misplacing of items repeatedly

Difficulty reading or writing

Getting lost/not knowing the current location

Loss of interest in people or activities

Changes in personality or behavior (mood swings, anger, depression, anxiety, etc.)

Poor judgment or inability to perceive dangerous situations

Parkinson’s Disease Dementia

Parkinson’s disease dementia is defined by the Alzheimer’s Association as “a decline in thinking and reasoning skills that develops in some people living with Parkinson’s at least a year after diagnosis.” Not all people who have Parkinson’s disease will have Parkinson’s dementia. The cause isn’t known, though brain changes resulting from Parkinson’s may play a role in its development.

Symptoms of Parkinson’s dementia may include:

Visual hallucinations

Delusions (paranoia)

Changes in memory and concentration

Sleep disturbances

Changes in behavior (depression, irritability, anger, etc.)

Muffled speech/difficulty speaking

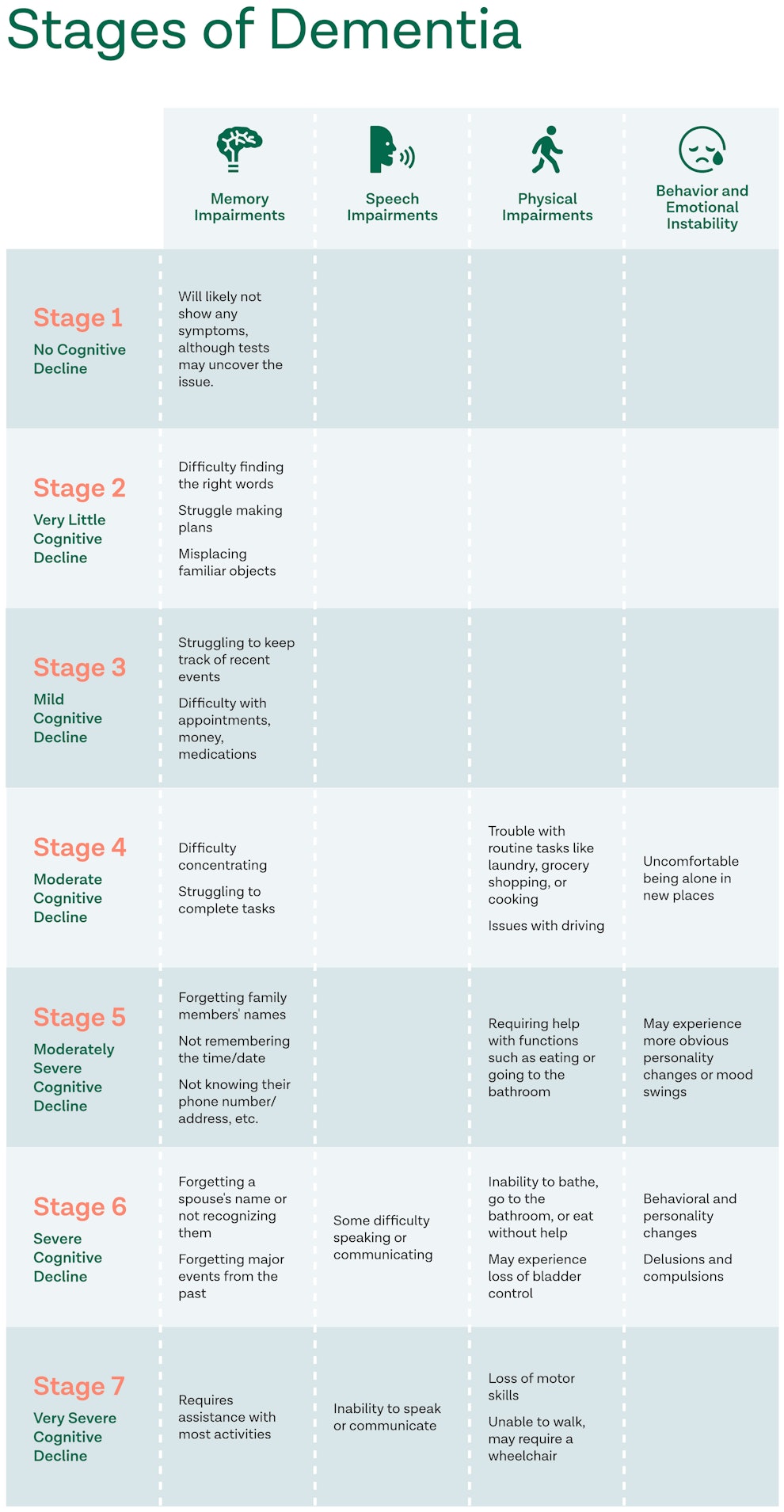

Stages of Dementia

Stage 1: No Cognitive Decline

In this stage, a person will likely not show any dementia symptoms. There is a possibility tests could reveal an issue.

This is often a time when loved ones can start the planning process with the person on how to proceed as the disease progresses.

Stage 2: Very Little Cognitive Decline

During the early stages of dementia, a person may only experience slight changes in behavior but will still be able to maintain independence.

Some signs include:

- Difficulty finding the right words to use

- Difficulty making plans

- Small memory problems, like misplacing familiar objects

Stage 3: Mild Cognitive Impairment

At this stage, it may become more apparent that the person has small changes in their reasoning/thinking abilities. This is also the stage that loved ones may begin to notice issues.

Some signs include:

- Not remembering plans made

- Beginning stages of memory loss

- Struggling to keep track of dates or recent events/conversations

- More difficulty in keeping appointments, managing money, or medications

- Slight difficulty concentrating

Note: Not everyone with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) has Alzheimer’s disease. If symptoms of MCI are present, it’s important to consult with a doctor as the procedures that diagnose preclinical Alzheimer’s disease can also determine if the MCI is unrelated to Alzheimer’s.

Stage 4: Moderate Cognitive Decline

This stage may introduce more obvious changes in their reasoning and thinking abilities. They will still remember most of their past but may struggle more with day-to-day situations.

Some signs include:

- Forgetting where common things are, such as their phone or glasses

- Trouble with routine tasks like laundry, grocery shopping, or cooking

- Forgetting recent events

- Difficulty concentrating

- Issues with driving

- Uncomfortable being alone in new places

- Struggling to complete or follow through with tasks

Stage 5: Moderately Severe Cognitive Decline

This stage will show signs of more distinct memory loss and may notice a moderately severe decline in physical abilities.

Some signs include:

- Not remembering certain family members’ names

- Not knowing the time or date

- Not knowing where they are, their phone number or address, etc.

- May experience more obvious personality changes or mood swings

- Requiring help with functions such as eating or going to the bathroom

Stage 6: Severe Cognitive Decline

This stage will include severe memory loss, such as forgetting a spouse’s name or not recognizing them. This stage will require constant care, either from a family member or a healthcare provider.

Some signs include:

- Inability to carry out tasks like bathing, going to the bathroom, or eating without assistance

- Forgetting major events from the past

- Personality and behavioral changes

- Delusions and compulsions

- Some difficulty speaking or communicating

- May experience loss of bladder control

Stage 7: Very Severe Cognitive Decline

This stage, also referred to as late-stage dementia, will likely include the person not communicating or responding much.

In addition to previous stages, some signs include:

- Loss of motor skills

- Inability to speak or communicate

- Unable to walk, may require a wheelchair

- Requires assistance with most activities

How Fast Does Dementia Progress?

Dementia is often labeled a “progressive disease” meaning that symptoms will continue to develop and worsen with time. However, the specific timeline of how quickly dementia progresses will depend on a few factors, including:

Type of dementia: certain types of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, tend to progress slower than others.

Age: contrary to popular belief, an older adult diagnosed with dementia will likely have a slower development of symptoms than a younger (under 65) adult.

Other medical conditions: if a person has other medical conditions, such as heart disease, it could increase the progression of dementia symptoms.

How Long Can a Person Live With Dementia?

A person diagnosed with dementia will likely live for years with the condition. The length of time a person lives with dementia depends on factors such as age, other health conditions, and the type of dementia. The general life expectancy for certain types of dementia is as follows:

Alzheimer’s disease: 8–10 years (though some have reported living 15–20 years)

Lewy bodies dementia: about 6 years

Vascular dementia: about 5 years

Frontotemporal dementia: about 6–8 years

When To See a Healthcare Provider

Given that noticeable dementia symptoms typically do not appear until a few stages in, it can be difficult to determine when to see a healthcare provider. Some indicators may include:

If the person has a family history of dementia: despite not having noticeable symptoms, a person may choose to see a healthcare provider if there is a family history. Tests may be able to pick up on early stages and can allow some time to prepare and discuss how to approach later stages as dementia progresses.

If a person starts experiencing consistent forgetfulness or personality changes: while early symptoms may be difficult to distinguish from typical aging, a person may want to see a healthcare provider if they experience forgetfulness more than usual, or if family members begin to sense a noticeable difference in their behavior or cognitive skills.

If a primary care provider (PCP) suggests seeing a specialist: typically, seeing a primary care provider is the first step in behavioral changes. However, if your PCP recommends consulting a specialist, such as a neurologist or a geriatrician, this is the next step to determining a dementia diagnosis.

How Is Dementia Diagnosed?

There isn’t an official test to diagnose dementia, especially since “dementia” is a broad term that groups a variety of different diseases. Some tests can be run to help determine if dementia is present such as:

Cognitive tests: a PCP may test memory, cognitive skills, language skills, and other aspects to determine the stage of a person’s dementia (if present).

Brain scans: scans such as a CT or MRI (that can determine evidence of stroke or bleeding in the brain) or a PET scan (which can determine if certain proteins have been deposited in the brain) can potentially help diagnose dementia.

Laboratory tests: some blood tests may be able to indicate if symptoms are a result of another issue, such as low vitamin deficiency or issues with the thyroid gland. This can determine whether to continue with a dementia diagnosis.

Note: Specifically relating to Alzheimer’s disease, certain biomarkers exist to give a more accurate diagnosis.

How To Treat Dementia

There currently isn’t a cure for dementia, so treatment often focuses on managing dementia symptoms which can vary from patient to patient as the causes of dementia depend on the type of dementia one has.

Medications

Some medications often used to treat symptoms include:

Cholinesterase inhibitors: such as donepezil (Aricept), rivastigmine (Exelon), and galantamine (Razadyne) work to help improve memory and judgment by boosting levels of a chemical messenger in the brain.

Memantine (Namenda): this medication works to regulate glutamate activity, another chemical messenger in the brain that aids in memory and learning.

Other medications: other medications may be prescribed to focus on other symptoms, including depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, and others.

Therapies

Many dementia symptoms may be approached with therapies that don’t include medication, such as:

Occupational therapy: An occupational therapist can teach coping behaviors and offer advice on how to make the home a safer place. This can help prevent accidents as well as prepare as dementia progression continues.

Altering and simplifying environment: options here may include reducing clutter or hiding unsafe objects in a person with dementia’s home. This can help prevent accidents as well as allow the person to focus better without becoming too distracted. Monitoring systems can also be advised, as they can alert if the person with dementia wanders.

Simplifying tasks: This will likely include breaking down basic tasks to make them easier, as well as creating a consistent routine to reduce confusion for the person with dementia.

How To Care For Someone With Dementia

Once a person is diagnosed with dementia, it’s important to determine what type of care is needed and can be provided.

Making Medical Decisions

Due to the impact on memory loss and reasoning skills, especially for a person diagnosed with moderate to late-stage dementia, a caregiver needs to be able to make informed medical decisions on the person’s behalf. Some things to keep in mind include:

Setting up a dementia/end-of-life plan: if dementia is caught early on, or if there is a family history of dementia, putting together a document or plan laying out the person’s wishes can be an invaluable asset down the line.

Including quality of life in decision-making: while dementia has no cure, certain medications and treatments may delay or relieve symptoms for a period of time. Weighing the pros and cons of these treatments and how they will benefit/affect the person is worth considering.

Considering all aspects: it’s important to assess all benefits, side-effects, and risks associated with end-of-life dementia care. It may be more important to prioritize a person’s comfort over extending their life span, depending on the circumstances.

How Caregivers Can Provide Support

Trying to determine the best way to care for a loved one with dementia, especially in stages with severe memory loss, can seem difficult. Some ways a caregiver can provide support include:

Engaging a person’s senses: while this may vary from person to person, it can be calming and beneficial to target the senses with familiar comforts, such as playing music they’ve enjoyed, calming scents, or giving a massage (if they are comfortable with being touched) can all be great ways to bring comfort.

Being present: for some, just having a person present can be comforting and reassuring.

Getting recommendations from hospice care: whether or not you ever choose to use hospice care, speaking with workers can provide suggestions on how best to care for a late-stage dementia patient.

Caregiver Resources

Being a caregiver can be emotionally, physically, and mentally draining on a person, regardless of how much love there is for the person with dementia. It’s important to have support and resources available for caregivers. Some resources include:

ALZConnected (this online support group also includes other types of dementia, not just Alzheimer’s)

FAQ

Why should I get screened for dementia and Alzheimer’s early?

An early diagnosis allows more opportunities for you to slow the cognitive decline Alzheimer’s induces. Not to mention, you could participate in a wider set of clinical trials that present the latest medical advancements in the fight against Alzheimer’s that stem from intensive research on how various types of dementia affect the brain.

Sources

- https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-are-signs-alzheimers-disease

- https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-are-frontotemporal-disorders#causes

- https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-lewy-body-dementia-causes-symptoms-and-treatments#signs

- https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/vascular-dementia

- https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia/types-of-dementia/parkinson-s-disease-dementia

- https://www.cdc.gov/aging/dementia/index.html

- https://compassionandchoices.org/resource/dementia-7-stages

- https://www.dementiacarecentral.com/aboutdementia/facts/stages/

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/difference-between-dementia-and-alzheimer‑s#

- https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/how-dementia-progresses/progression-stages-dementia

- https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/end-life-care-people-dementia

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/in-depth/alzheimers-stages/art-20048448

- https://alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/diagnosis/why-get-checked

Become a patient

Experience the Oak Street Health difference, and see what it’s like to be treated by a care team who are experts at caring for older adults.